I was very intentional about whose voices I amplified and about making sure the ideas came from people in the community.The neighbors already had a lot of knowledge; part of it was asking what they wanted to see there. What was their vision? What did they have the skills to do and what could we do together? We built programs based on that. I think that’s what made Bayer Farm really strong.

How did it all start for you – when did you first get connected to LandPaths?

I actually got a phone call one day from Craig. I had never heard about LandPaths before that – I didn’t know what the conservation movement was, I didn’t know what the Open Space District was. Craig had heard of me because, at the time, I was participating in community meetings and doing youth activities around Roseland, where I grew up. LandPaths was planning the Bayer Farm project, though it wasn’t called that yet, they just knew they wanted to have a place in the community where people could access LandPaths’ programming, a sort of a portal in Southwest Santa Rosa. Craig asked if he could meet with me and discuss the project.

We met at my mom’s house in Roseland and walked over to a piece of land that was across the street from my former elementary school. It was a dirty field, never something I’d noticed or even looked at because there was a fence there and I’m not the kind of person who would hop over people’s fences to go visit nature. And suddenly he’s telling me we’re going to be able to go on to that land.

What was the conservation movement like when you joined LandPaths in 2007?

I had zero contact with anybody from that world. I’m an environmentally minded person, and my family raised me with the ethics that nature is important and beautiful and should be cared for. I was really lucky because both of my parents were kind of hippies and they do appreciate nature. We recycled. It wasn’t that my values weren’t aligned, but nobody was sending brochures to our neighborhood or anything like that. I think most of the schools in Santa Rosa had a thing called outdoor education, but we didn’t get to do that. There were probably a couple field trips but no, there wasn’t any contact with what you would call the environmental movement.

At the time that I joined LandPaths there wasn’t a lot of diversity. I was a very unique hire. There wasn’t a lot of intention towards involving low-income, younger, non-white communities in what is called the conservation movement.

At meetings and conferences, I was often the only Latina, and at least a decade or two younger than most everybody else. It wasn’t a group of people or culture that I was really familiar with. But people were kind, at least at LandPaths, generally, and they were trying to work on their blind spots. Lee and Craig were very good at listening. They had me there for a specific reason. It wasn’t like, “Oh look, we hired a Latina, that’s good enough.” It was so I could help bring in these other voices and these other perspectives. They created an environment where I could do my work.

What is some of the LandPaths programming that you started that continues today?

I had no idea what I was doing at all or what I was supposed to be doing. [The start of Bayer Farm] was very organic. Craig basically said, “Hey, we cut a hole in the fence, we need to get people out there.” I started making calls and giving LandPaths ideas. Planting food made sense to me, maybe because my mom always had her little garden and it’s a really common thing in the neighborhood and culturally. People would have corn growing in their front yards; they would have pots with food growing even in the apartments.

I called up a program that worked with students from a continuation high school and asked them, “Do you want to come and do something on the land?” They said yes, and brought the students. LandPaths brought the plant starts. We went out to Bayer Farm and all planted together. It was really beautiful. It was in August, but the plants ended up growing anyway.

Letting people know Bayer was open was the first step. I used to chase people down the street, saying, “Hey, you can come in here! You are literally allowed to come in here!” And then, we would talk about plants and nature and let the kids run around. I was very intentional about whose voices I amplified and about making sure the ideas came from the neighbors and the people in the community.The neighbors already had a lot of knowledge; part of it was asking what they wanted to see there. What was their vision? What did they have the skills to do and what could we do together? We built programs based on that. I think that’s what made Bayer Farm really strong.

At the time, Jonathan Glass ran the outings program. He and I were talking, and he basically said there was nothing in our contract that says which language we had to do our outings in. He and I picked a couple properties and thought about what a hike led in Spanish should be like to attract participants. Jonathan and another staff member took me to Taylor Mountain, which you can see from Roseland. My whole life, I’d wanted to go there, but there was a bunch of fences. I asked them, “What should I do?” They told me to just sit there and enjoy the nature. I sat there and observed a bird flying and I was like, “Wow, I can’t believe they are paying me to just sit in nature.” But now I get it. I had to experience that connection so that I could help other people understand how healing and wonderful it is.

So that was how Vamos Afuera (“Let’s Go Outside”) started. It really was part of this effort to connect people and deepen their relationships with open spaces. The Open Space District funded these programs because taxpayers speak all different languages and come from different backgrounds and we’re all paying for these lands. A lot of people in our community don’t speak English, and I spoke Spanish. My role was to connect this specific community with the programming.

How has being part of LandPaths impacted your life?

It really did teach me a lot about the natural world. I especially loved learning about riparian corridors. I see them everywhere now! I didn’t a creek runs through Roseland –I used to think it was just a storm drain. But it was also the first job I had where my ideas mattered. Who I was, where I was from, had a bearing on the overall organizational goals. I could participate in reaching goals and having a vision. That was amazing to me because that had never happened before. I had a college degree, but I had dropped out twice, and finished with an adult degree completion program while I was working. I had a kid and I didn’t do internships, so I didn’t have that experience of being an important member of a team before LandPaths. It was amazing to be validated in that way.

It also really deepened my ties with my community. I got to meet so many people and do amazing things with them. It was such a gift to build these wonderful programs for and with my community.

I still remember standing on that sidewalk and looking over that fence with Craig and I got it right away. All he had to do was show me, “We get to go there now,” and I got understood what they were trying to do. That was a vision that really made sense to me: This is not something we build for people. This is our opportunity to build something greater with people. I think that is true across the boards with LandPaths, that’s what LandPaths does; it deepens relationships between each other and with the land, and those relationships are so important and interconnected.

What is your wish for the future of LandPaths and Sonoma County?

The world feels very different from when I joined LandPaths. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about climate change and how urgent it is. I think we’ve run out of time for incremental steps. We didn’t used to have fire season and now we do, and that’s not a change I am willing to just accept. It’s really critical that we as a species take urgent action and I really hope that all of us listen to our land and listen to what our land is saying. That is something I think about a lot for my children.

Part of being in a relationship is listening. It’s not enough to just set up some trails and go visit the nature and then come back to the city and forget about it. How can we move forward to have healthy relationships with the earth we live on? It’s critical that we have healthy relationships with each other so we can work collaboratively.

I hope that LandPaths is able to broaden the base even more. I feel like the indigenous community, in general, is ignored and disregarded. I’d like to see what guidance or preferences they have. LandPaths was able to successfully reach out to the Latino community. Are there other communities in this area that maybe don’t get the chance to visit nature? Is there a way to deepen those relationships so that we are all listening to and living on the land in healthy, balanced ways?

LandPaths is well positioned to help guide us there, because it’s much less of a transactional model. I would love for society to get back to being in relationship with the land. LandPaths is all about that.

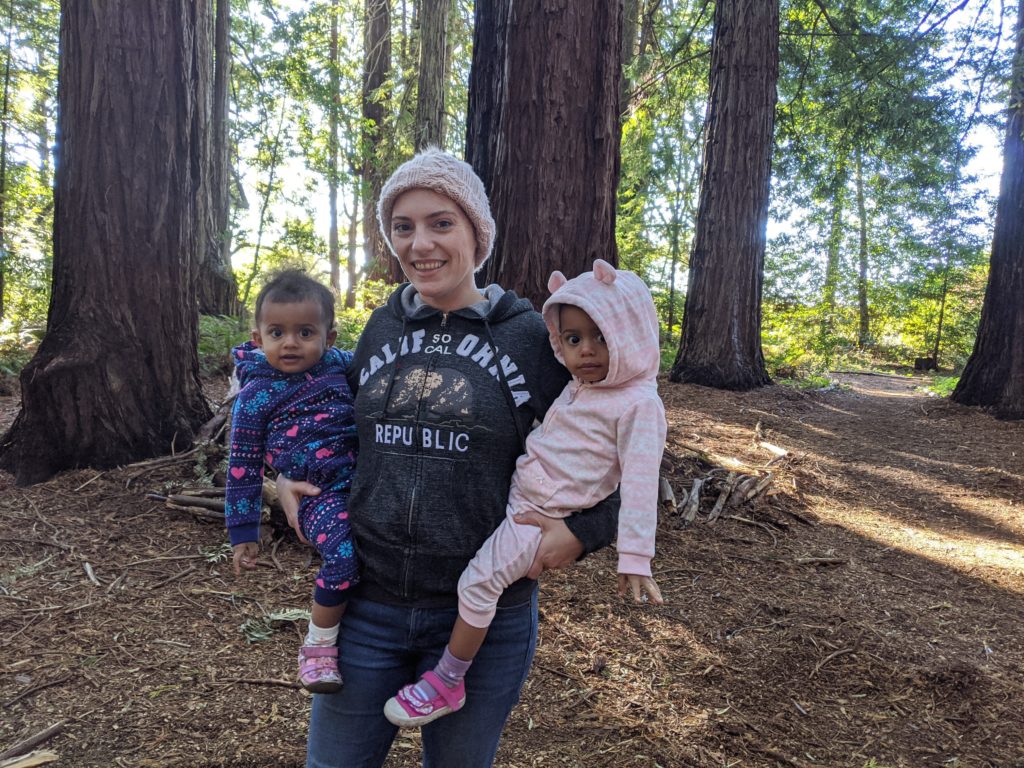

Magdalena with her twins at the Grove of Old Trees in 2020.

Magdalena’s four children at the Grove of Old Trees in 2020.